|

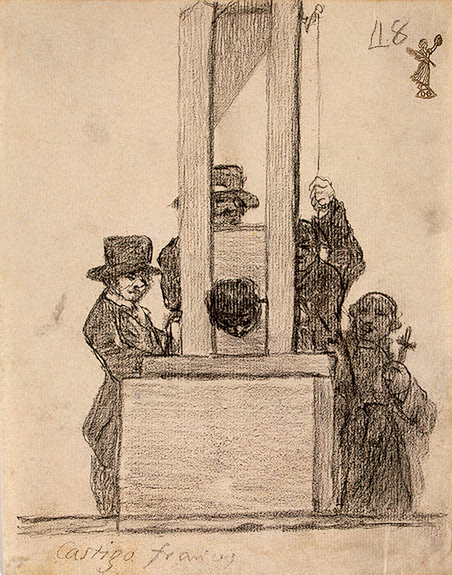

| Goya, "The French Penalty", c. 1824 |

Yet the pressures towards both cannot be overestimated. As we have seen with recent changes in sexual ethics, without a firm understanding of why these things are wrong, they soon become socially acceptable and then commonplace. Chesterton once joked that one might overcome the need for birth control by letting all the babies be born and then killing those one didn't like. He was attempting a reductio ad absurdum, but today influential philosophers are advocating infanticide in all seriousness.

So, what is intrinsically wrong with abortion and the "mercy killing" of human beings? We cannot understand this without some appreciation of the notion

of the human person. A human life begins at conception and ends with the loss of biological integrity at death. There is a small grey area in both cases, where we may not be quite sure whether life has begun or ended, but one should err on the side of caution. A human life, of course, has value for many reasons - a person who is loved, or has a great talent, or is playing an important social role, etc. has "added value" for all these reasons. The abortion advocates see only this kind of value, and argue that it may be outweighed or absent altogether in some cases. But each human life also has what might be termed an intrinsic value, which is infinite, simply by being what it is. Just as in mathematics, when we add a number to infinity, infinity does not get any larger, so in the case of human life, the addition of finite values to intrinsic value does not substantially affect the outcome, and so all human beings remain of equal value. Directly to act against a human life cannot be justified in the name of any good whatever.

This sort of argument is difficult to maintain without a belief in the existence of God as the creator and lover of man. It is from the infinity of God that the divine image acquires its infinite value, and by our direct relation to God that we transcend all other social relationships and all questions of utility. It would seem, therefore, that the abortion argument is unwinnable unless we first convert our opponent to a religious faith. We think of belief in God as creator, and in man as person, as matters of faith. In fact, though, not all beliefs are supernaturally infused, and these particular things are evident to human reason - that is why Catholics who argue for the banning of abortion are not merely trying to "impose their personal beliefs on others". Certainly faith strengthens and clarifies our understanding of these matters, but there are perfectly reasonable grounds for believing in the soul and in a Creator.

The "soul" is our word for the principle of unity that holds together the parts of a life and makes them parts of one entity. All living animals and plants have a soul, but human beings, since they are a rational animals, have a rational soul. This is not the same as having a "mind"; it is better described as having a self, an "I". The arguments can only be hinted at here. The ability to grasp truth implies a certain transcendence of biological cause and effect. The mere fact that it is the same "I" that feels a pain in my leg, a sweet sensation in my tongue and an itch in my scalp requires a single non-physical entity to own these experiences. There is also an argument from music - the ability to grasp a pattern across time indicates that the observer is not confined to a given temporal moment, as physical things are.

As for the Creator, the existence of something rather than nothing does not explain itself. The only thing that could "explain itself" in that sense is something whose essence is to exist, that logically could not not be. The universe, or any assembly of things that could be otherwise, is not such a thing. Such an entity, which we call God, would necessarily be invisible and would be the cause of the existence of all else. What can legitimately be said about it without self-contradiction has been carefully worked out by theologians such as Thomas Aquinas, and will not be repeated here. (Stephen Hawking, of course, has not followed these arguments. A sufficient refutation of his recent argument for atheism can be found in a forthcoming book by William E. Carroll from CTS entitled Creation and Science, and on the educational web-site of the Magis Center.

No comments:

Post a Comment